[Refresh] [Bottom] [Index] [Archive]

Sort by:

Image size:

R:38 / I:10 (sticky)

Welcome to the new When They /cry/ board! You can post Higurashi content without worrying about spoiling things. By default this board won't be showing up on /all/ or the front page. You can post about Umineko and Ciconia, too, but you should use spoiler options on those for the time being. This is something we can figure out together.

Welcome to the new When They /cry/ board! You can post Higurashi content without worrying about spoiling things. By default this board won't be showing up on /all/ or the front page. You can post about Umineko and Ciconia, too, but you should use spoiler options on those for the time being. This is something we can figure out together.

R:12 / I:7

I've read through the first four VNs twice now and I'm about to start the answer arc. Here are my thoughts. I'm not gonna return to this thread until after I get through the next four VNs.

It's really difficult to come up with hypotheses. When the VNs reach the omake scenes of the characters commentating on events and giving their opinions, what they say feels like it's light-years ahead of my thinking. I don't think I have any uncommon insights into background events, I only have a scattered summary of what I saw and mostly took at face value. I really want to go see other people's thoughts during their first-time reads because I don't know how they could have possibly figured stuff out.

My hypotheses:

¥ The main question the VNs pose is: "Is this all the work of humans, or is there something supernatural going on?". I believe there are supernatural things going on. There really is an Oyashiro-sama who can cause the volcanic gases to emerge if he is angered, Rika knows certain things about the future including how people will die, and demons exist and have magic powers. That doesn't mean I take the whole story about 'transcendents' as fact. Regarding demons: Demons are a mental presence that can wax or wane in strength, and can be resisted when they are weak. When they are strong, they change your values, making you a violent predator of mankind.

[s yen]¥ Someone on Kissu said something about guessing that some characters are in cahoots. I think maybe Tomitake was asked by Ooishi to help out with the latter's private investigations. That's why he takes pictures of Keiichi in VN 1 and why in VN 2 he guards the door for Miyo and co when they're inside the storehouse. Basically the things that Tomitake is inclined to do anyway (befriend Miyo, visit Hinamizawa for photography) benefit Ooishi so why not ask him for info on top, or to steer events Ooishi's way.[s yen]

Things I am actively confused about:

¥ What's the meaning of the second set of footsteps that Keiichi hears in VNs 1 and 3?

[s yen]¥ When Keiichi is getting his fur seal keychain back from Angel Mort, that's when Shion tells him about the epic tale of the Hinamizawa Dam War. Keiichi at the time is under the impression that it's Mion telling him these things.

The confusing part is that he never corrects this impression when he learns that Mion and Shion are indeed two different people, AND it's as if other people are under that impression too.

Shion in a later scene (the evening before Watanagashi) asks, did you hear this from my sister, she likes these kinds of 'epics'. But he heard about it from Shion, not Mion!!! I really wonder if something was lost in translation.

[s yen]¥ No clue what the knocking sound is about in VN 2 when Keiichi and co are inside the ritual implement storehouse.

[s yen]¥ Miyo was around and active when she was supposed to be dead. Also how did Miyo get from driving around late at night in VN 3 to being burned alive in the barrel.

[s yen]¥ I don't know the capabilities of demons. Are they body doubles, or do they only possess people. Can they disguise themselves as anyone? Can they possess corpses and bring them back to life?

Basically I'm confused about everything in VN 3 starting from when Keiichi resolves to kill Teppei. At least some stuff must have really happened, because Satoshi's baseball bat is not in its usual place.

I don't want to claim that demons have too many powers because then there are way too many degrees of freedom to pin down anything that happens in the story.[s yen]

Random thoughts/observations:

¥ Keiichi is an unreliable narrator in one way, if he doesn't notice something the game won't point it out to you. He doesn't notice his mother calling for him in VN 1 when he's engrossed in a phone call. I think him not noticing the knocking sound in VN 2 inside the storehouse was an example.

[s yen]¥ I don't know if Mion believes in supernatural or not. In VN 1 she acts like she doesn't in contrast to Rena taking it very seriously, but in VN 2 she calls Satoko a cursed child.

[s yen]¥ Rika carries around a syringe all the time, maybe it contains something that can knock her unconscious so she doesn't have to be awake during her watanagashi.

[s yen]¥ Mion's grandmother was probably orchestrating a lot of stuff such as the needle in the mochi that Mion admitted to putting inside in VN 1.

[s yen]¥ The manager that Rena and Mion refer to near the end of VN 1 is probably doctor Irie, who's also the manager of the baseball team.

[s yen]¥ The volcanic gas eruption doesn't happen every time, I think in both VNs 1 and 2 enough days pass after Watanagashi festival that it rules it out happening on the timeframe in which it happens in VNs 3 and 4.

[s yen]¥ In VN 3, what I think happened to set up the story was: Teppei's lover was against the Sonozakis and caused their yakuza money to disappear, the lover gets waganashi'd in revenge and is found in the sewer in the prologue, Teppei gets spooked and comes back to Hinamizawa. I guess it's an intentional divergence point that didn't happen in VNs 1 and 2.

[s yen]¥ I think Keiichi got stuck with the needle at the end of VN 1 and he didn't notice it. Then it affects him when he's in the phone booth.

[s yen]¥ There's a lot of fanarts of Rena holding a machete. But no such scene has happened yet.[s yen]

I've read through the first four VNs twice now and I'm about to start the answer arc. Here are my thoughts. I'm not gonna return to this thread until after I get through the next four VNs.

It's really difficult to come up with hypotheses. When the VNs reach the omake scenes of the characters commentating on events and giving their opinions, what they say feels like it's light-years ahead of my thinking. I don't think I have any uncommon insights into background events, I only have a scattered summary of what I saw and mostly took at face value. I really want to go see other people's thoughts during their first-time reads because I don't know how they could have possibly figured stuff out.

My hypotheses:

¥ The main question the VNs pose is: "Is this all the work of humans, or is there something supernatural going on?". I believe there are supernatural things going on. There really is an Oyashiro-sama who can cause the volcanic gases to emerge if he is angered, Rika knows certain things about the future including how people will die, and demons exist and have magic powers. That doesn't mean I take the whole story about 'transcendents' as fact. Regarding demons: Demons are a mental presence that can wax or wane in strength, and can be resisted when they are weak. When they are strong, they change your values, making you a violent predator of mankind.

[s yen]¥ Someone on Kissu said something about guessing that some characters are in cahoots. I think maybe Tomitake was asked by Ooishi to help out with the latter's private investigations. That's why he takes pictures of Keiichi in VN 1 and why in VN 2 he guards the door for Miyo and co when they're inside the storehouse. Basically the things that Tomitake is inclined to do anyway (befriend Miyo, visit Hinamizawa for photography) benefit Ooishi so why not ask him for info on top, or to steer events Ooishi's way.[s yen]

Things I am actively confused about:

¥ What's the meaning of the second set of footsteps that Keiichi hears in VNs 1 and 3?

[s yen]¥ When Keiichi is getting his fur seal keychain back from Angel Mort, that's when Shion tells him about the epic tale of the Hinamizawa Dam War. Keiichi at the time is under the impression that it's Mion telling him these things.

The confusing part is that he never corrects this impression when he learns that Mion and Shion are indeed two different people, AND it's as if other people are under that impression too.

Shion in a later scene (the evening before Watanagashi) asks, did you hear this from my sister, she likes these kinds of 'epics'. But he heard about it from Shion, not Mion!!! I really wonder if something was lost in translation.

[s yen]¥ No clue what the knocking sound is about in VN 2 when Keiichi and co are inside the ritual implement storehouse.

[s yen]¥ Miyo was around and active when she was supposed to be dead. Also how did Miyo get from driving around late at night in VN 3 to being burned alive in the barrel.

[s yen]¥ I don't know the capabilities of demons. Are they body doubles, or do they only possess people. Can they disguise themselves as anyone? Can they possess corpses and bring them back to life?

Basically I'm confused about everything in VN 3 starting from when Keiichi resolves to kill Teppei. At least some stuff must have really happened, because Satoshi's baseball bat is not in its usual place.

I don't want to claim that demons have too many powers because then there are way too many degrees of freedom to pin down anything that happens in the story.[s yen]

Random thoughts/observations:

¥ Keiichi is an unreliable narrator in one way, if he doesn't notice something the game won't point it out to you. He doesn't notice his mother calling for him in VN 1 when he's engrossed in a phone call. I think him not noticing the knocking sound in VN 2 inside the storehouse was an example.

[s yen]¥ I don't know if Mion believes in supernatural or not. In VN 1 she acts like she doesn't in contrast to Rena taking it very seriously, but in VN 2 she calls Satoko a cursed child.

[s yen]¥ Rika carries around a syringe all the time, maybe it contains something that can knock her unconscious so she doesn't have to be awake during her watanagashi.

[s yen]¥ Mion's grandmother was probably orchestrating a lot of stuff such as the needle in the mochi that Mion admitted to putting inside in VN 1.

[s yen]¥ The manager that Rena and Mion refer to near the end of VN 1 is probably doctor Irie, who's also the manager of the baseball team.

[s yen]¥ The volcanic gas eruption doesn't happen every time, I think in both VNs 1 and 2 enough days pass after Watanagashi festival that it rules it out happening on the timeframe in which it happens in VNs 3 and 4.

[s yen]¥ In VN 3, what I think happened to set up the story was: Teppei's lover was against the Sonozakis and caused their yakuza money to disappear, the lover gets waganashi'd in revenge and is found in the sewer in the prologue, Teppei gets spooked and comes back to Hinamizawa. I guess it's an intentional divergence point that didn't happen in VNs 1 and 2.

[s yen]¥ I think Keiichi got stuck with the needle at the end of VN 1 and he didn't notice it. Then it affects him when he's in the phone booth.

[s yen]¥ There's a lot of fanarts of Rena holding a machete. But no such scene has happened yet.[s yen]

R:11 / I:10

A thread ranking Higurashi: When They Cry characters by how much they cry.

1. Hojo Satoko

The undisputed champion of Higurashi, dubbed "Miss Higurashi" by Ryukishi himself, is none other than Hojo Satoko-chan. Notorious for her ceaseless bouts of crying, often punctuated by beckons for her "Nii-nii," Satoko is a veritable fountain of tears. In recent years she has managed to overcome her affliction through willpower, but it's not nearly enough to dethrone her. All hail the greatest Higurashi When They Crier!

2. Maebara Keiichi

He might like to posit a cool exterior, but the fact is our favourite male lead is actually a total crybaby, so much so that it lands him the coveted second spot on our list. He cries over his friends in Onikakushi, cries over Rika and Satoko's deaths in Watanagashi, cries over Satoko's abuse in Tatarigoroshi, cries over accusations of child abuse from Rena and flashbacks about Mion in Tsumihoroboshi... I mean really, how did this guy even manage to get anything done if he was busy bawling his eyes out so much? I guess in the world of When They Cry being a chronic crier is actually advantageous.

3. Sonozaki Mion

Keiichi told her she wasn't his friend anymore. She cried. Keiichi didn't give her a toy doll because she's too boyish. She cried. Keiichi accused her and her family of being complicit in a village-wide conspiracy of abuse against Satoko. She cried. What a baby! For being the heir to the powerful seat of the village leader she sure is a wuss! Third place was always guaranteed.

4. Sonozaki Shion

Shion does her fair share of crying, but, honestly, her moments of weakness are well-deserved. Tortured by her family, her almost-boyfriend seemingly murdered for inner-village politicking, her adopted sister stolen by her abusive uncle while the authorities ignore the facts. Her bold and steadfast personality often overshadows these moments enough to maybe fool you into forgetting them, but she has her moments of utter vulnerability. And of course there's her death scene in Meakashi, when she cries and begs for Satoko's forgiveness before throwing herself off the edge of the building. Even I cried.

5. Ryugu Rena

My guess is she'd be crying a lot more if she wasn't an inch away from giving into literal insanity most of the time. If she encounters something intense enough to warrant a good cry, she'll usually just instead start mumbling off into some imperceptible distance and scratching at her neck. What's up with that? Can't ever trust gingers, that's what I always say.

6. Furude Hanyuu

Literally who?

7. Furude Rika

A cynical and malicious drunk, far too heartless to ever let her true feelings show on her sleeve. If you see her crying, approach with caution, for hers are likely crocodile tears. If she is ever really crying, it's probably because she failed in attaining a goal after doing nothing at all to achieve it. What a tragedy.

8. Hojo Satoshi

Satoshi does not cry. He's too busy getting things done. He suppresses his emotions to superhuman levels, and in every fragment always succeeds in overpowering his weaknesses and buying the teddy bear he wants to gift to his little sister. He's cruelly rewarded with medical intervention and likely frequent molestation at the hands of Takano Miyo. But in the grand game of fate that spans across all universes, he can hold his head high and claim a greater victory than this list implies.

A thread ranking Higurashi: When They Cry characters by how much they cry.

1. Hojo Satoko

The undisputed champion of Higurashi, dubbed "Miss Higurashi" by Ryukishi himself, is none other than Hojo Satoko-chan. Notorious for her ceaseless bouts of crying, often punctuated by beckons for her "Nii-nii," Satoko is a veritable fountain of tears. In recent years she has managed to overcome her affliction through willpower, but it's not nearly enough to dethrone her. All hail the greatest Higurashi When They Crier!

2. Maebara Keiichi

He might like to posit a cool exterior, but the fact is our favourite male lead is actually a total crybaby, so much so that it lands him the coveted second spot on our list. He cries over his friends in Onikakushi, cries over Rika and Satoko's deaths in Watanagashi, cries over Satoko's abuse in Tatarigoroshi, cries over accusations of child abuse from Rena and flashbacks about Mion in Tsumihoroboshi... I mean really, how did this guy even manage to get anything done if he was busy bawling his eyes out so much? I guess in the world of When They Cry being a chronic crier is actually advantageous.

3. Sonozaki Mion

Keiichi told her she wasn't his friend anymore. She cried. Keiichi didn't give her a toy doll because she's too boyish. She cried. Keiichi accused her and her family of being complicit in a village-wide conspiracy of abuse against Satoko. She cried. What a baby! For being the heir to the powerful seat of the village leader she sure is a wuss! Third place was always guaranteed.

4. Sonozaki Shion

Shion does her fair share of crying, but, honestly, her moments of weakness are well-deserved. Tortured by her family, her almost-boyfriend seemingly murdered for inner-village politicking, her adopted sister stolen by her abusive uncle while the authorities ignore the facts. Her bold and steadfast personality often overshadows these moments enough to maybe fool you into forgetting them, but she has her moments of utter vulnerability. And of course there's her death scene in Meakashi, when she cries and begs for Satoko's forgiveness before throwing herself off the edge of the building. Even I cried.

5. Ryugu Rena

My guess is she'd be crying a lot more if she wasn't an inch away from giving into literal insanity most of the time. If she encounters something intense enough to warrant a good cry, she'll usually just instead start mumbling off into some imperceptible distance and scratching at her neck. What's up with that? Can't ever trust gingers, that's what I always say.

6. Furude Hanyuu

Literally who?

7. Furude Rika

A cynical and malicious drunk, far too heartless to ever let her true feelings show on her sleeve. If you see her crying, approach with caution, for hers are likely crocodile tears. If she is ever really crying, it's probably because she failed in attaining a goal after doing nothing at all to achieve it. What a tragedy.

8. Hojo Satoshi

Satoshi does not cry. He's too busy getting things done. He suppresses his emotions to superhuman levels, and in every fragment always succeeds in overpowering his weaknesses and buying the teddy bear he wants to gift to his little sister. He's cruelly rewarded with medical intervention and likely frequent molestation at the hands of Takano Miyo. But in the grand game of fate that spans across all universes, he can hold his head high and claim a greater victory than this list implies.

R:100 / I:62

I will post updates in this thread as I read through it. Someone said somewhere I should remember the red text, so maybe I'll take a screenshot of it every time and also make other screenshots and post them in the thread as I talk about it and maybe other people can talk about stuff (and please don't spoil things, although Gou/Sotsu already did that to an extent I feel).

I'm using some PS3 patch thing with the 'Witch Hunt'. I do find the original Ryukishi07 portraits kind of charming, but also distracting, so I'm going with the PS3 versions.

It's time to hopefully completely lose my connection to reality for a period of time again. I love that feeling.

To be continued...

I'm reading Umineko finally!

Alright, after severe procrastination going back years I finally got my setup going where I have my drawing tablet suspended over my head in bed and I have a game controller in my hand. Alas, I'm getting older and I can't really spend 15 hours a day with my arms in the air for weeks at a time and not get sore arms, so I was waiting until I could get this setup to read in bed before getting back into VNs seriously.I will post updates in this thread as I read through it. Someone said somewhere I should remember the red text, so maybe I'll take a screenshot of it every time and also make other screenshots and post them in the thread as I talk about it and maybe other people can talk about stuff (and please don't spoil things, although Gou/Sotsu already did that to an extent I feel).

I'm using some PS3 patch thing with the 'Witch Hunt'. I do find the original Ryukishi07 portraits kind of charming, but also distracting, so I'm going with the PS3 versions.

It's time to hopefully completely lose my connection to reality for a period of time again. I love that feeling.

To be continued...

R:5 / I:2

Question for >>>/qa/115969

Do you still have this set up? I tried to get it running on my machine, but I suck dick and this stuff and kept running into endless errors. Asking 'cause I ran into this documentary(?) on Umineko from a NHK show on otaku stuff and would like to see what they're talking about, exactly:

https://archive.org/details/magnetumineko

Seems some guy on on a discord server gave it a go five years ago but his video with its half translation has been taken down since then.

Question for >>>/qa/115969

Do you still have this set up? I tried to get it running on my machine, but I suck dick and this stuff and kept running into endless errors. Asking 'cause I ran into this documentary(?) on Umineko from a NHK show on otaku stuff and would like to see what they're talking about, exactly:

https://archive.org/details/magnetumineko

Seems some guy on on a discord server gave it a go five years ago but his video with its half translation has been taken down since then.

R:6 / I:6

There's a very interesting short story about the experimental works of a fictional author, An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain, that really reminded me of R07, and wanted to share it. It's by Borges.

Quain, recently deceased and mostly unsuccessful, first writes a mystery novel: The God of the Labyrinth, an otherwise regular inquiry into an assassination, save for a sentence at the end:

>‘Everyone thought that the encounter of the two chess players was accidental.’ This phrase allows one to understand that the solution is erroneous. The unquiet reader re-reads the pertinent chapters and discovers another solution, the true one. The reader of this singular book is thus forcibly more discerning than the detective.

Supremely relevant to Umineko, the reader figuring it out while the detective fails to do so. But even more relevant is his next work, April March.

April March (the book itself) is composed like a game:

>In judging this novel, no one would fail to discover that it is a game; it is only fair to remember that the author never considered it anything else. ‘I lay claim in this novel,’ I have heard him say, ‘to the essential features of all games: symmetry, arbitrary rules, tedium.’

It's made up of thirteen chapters, in a structure arranged as shown in this diagram:

https://files.catbox.m

This one's a doozy. The important part is that there's a fundamental chapter, Z, that is shared among all the stories told inside the book. It's comparable to the intial state of the gameboard or the outcome of Rokkenjima. Then, Y1, Y2, and Y3 are separate possible scenarios that branch out from there, and each of them branch once more into three more, X from 1 to 9. That's what the brackets represent. So what you have is one book that contains within it nine different stories that share major unavoidable plot elements and are alternate universes of each other, much like what happens with fragments. Furthermore,

>Whoever reads the sections in chronological order (for instance: X3, Y1, Z) will lose the peculiar savour of this strange book. Two narratives —X7, X8— lack individual worth; mere juxtaposition lends them effectiveness...

>I do not know if I should mention that once April March was published, Quain regretted the ternary order and predicted that whoever would imitate him would choose a binary arrangement:

Which is what we see in the pairings of question and answer arcs. Despite Quain's text having a "rage for symmetry" as Borges writes that Schopenhauer wrote about Kant, it seems from the gloss that it is not as internally unified as Higurashi and Umineko are (and they already go to many places).

It really stood out to me, it's like seeing someone make a site for the library of Alexandria that really has an infinity of incoherent text just as he described it, except seemingly by pure coincidence. Then there's Death and the Compass making fun of detective novels in general, where a man spends three months reading up on Hebrew theology to unravel a murder, only to get totally baited. Maybe that's another place Umineko telepathically got material from.

There's a very interesting short story about the experimental works of a fictional author, An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain, that really reminded me of R07, and wanted to share it. It's by Borges.

Quain, recently deceased and mostly unsuccessful, first writes a mystery novel: The God of the Labyrinth, an otherwise regular inquiry into an assassination, save for a sentence at the end:

>‘Everyone thought that the encounter of the two chess players was accidental.’ This phrase allows one to understand that the solution is erroneous. The unquiet reader re-reads the pertinent chapters and discovers another solution, the true one. The reader of this singular book is thus forcibly more discerning than the detective.

Supremely relevant to Umineko, the reader figuring it out while the detective fails to do so. But even more relevant is his next work, April March.

April March (the book itself) is composed like a game:

>In judging this novel, no one would fail to discover that it is a game; it is only fair to remember that the author never considered it anything else. ‘I lay claim in this novel,’ I have heard him say, ‘to the essential features of all games: symmetry, arbitrary rules, tedium.’

It's made up of thirteen chapters, in a structure arranged as shown in this diagram:

https://files.catbox.m

This one's a doozy. The important part is that there's a fundamental chapter, Z, that is shared among all the stories told inside the book. It's comparable to the intial state of the gameboard or the outcome of Rokkenjima. Then, Y1, Y2, and Y3 are separate possible scenarios that branch out from there, and each of them branch once more into three more, X from 1 to 9. That's what the brackets represent. So what you have is one book that contains within it nine different stories that share major unavoidable plot elements and are alternate universes of each other, much like what happens with fragments. Furthermore,

>Whoever reads the sections in chronological order (for instance: X3, Y1, Z) will lose the peculiar savour of this strange book. Two narratives —X7, X8— lack individual worth; mere juxtaposition lends them effectiveness...

>I do not know if I should mention that once April March was published, Quain regretted the ternary order and predicted that whoever would imitate him would choose a binary arrangement:

Which is what we see in the pairings of question and answer arcs. Despite Quain's text having a "rage for symmetry" as Borges writes that Schopenhauer wrote about Kant, it seems from the gloss that it is not as internally unified as Higurashi and Umineko are (and they already go to many places).

It really stood out to me, it's like seeing someone make a site for the library of Alexandria that really has an infinity of incoherent text just as he described it, except seemingly by pure coincidence. Then there's Death and the Compass making fun of detective novels in general, where a man spends three months reading up on Hebrew theology to unravel a murder, only to get totally baited. Maybe that's another place Umineko telepathically got material from.

R:52 / I:23

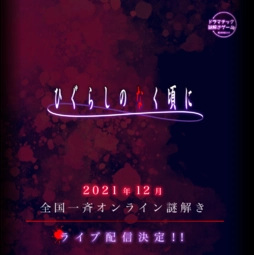

To celebrate Watanagashi (and /cry/'s yearly return) we're going to stream the original Higurashi anime and all its many episodes! It will never fit in one or even 4 nights, so we're going to do it as weeks-long event with like 4-6 episodes each weekday.

Standard stream start time of 7PM EST / 12AM UTC (EDIT: MOVED BACK AN HOUR)

Question Arc: 12th through 16th

Answer Arc: 19th through 23rd

Specials: 26th+

If you don't know what Higurashi is like, well... It's happy, but also sad and very violent. Extremely good characters and it's very emotional and the music is fantastic, including the anime-exclusive stuff. The ideal experience is to read it, but if you don't have about 80 hours to devote to that then you should at least watch the anime. It's one of things you really need to experience.

After all this concludes I think I'll move this thread to /cry/ for archival purposes

Higurashi (Deen) Streams

Alright, it's time to /cry/!To celebrate Watanagashi (and /cry/'s yearly return) we're going to stream the original Higurashi anime and all its many episodes! It will never fit in one or even 4 nights, so we're going to do it as weeks-long event with like 4-6 episodes each weekday.

Standard stream start time of 7PM EST / 12AM UTC (EDIT: MOVED BACK AN HOUR)

Question Arc: 12th through 16th

Answer Arc: 19th through 23rd

Specials: 26th+

If you don't know what Higurashi is like, well... It's happy, but also sad and very violent. Extremely good characters and it's very emotional and the music is fantastic, including the anime-exclusive stuff. The ideal experience is to read it, but if you don't have about 80 hours to devote to that then you should at least watch the anime. It's one of things you really need to experience.

After all this concludes I think I'll move this thread to /cry/ for archival purposes

R:7 / I:2

Is there a character stronger than Auaurora?

And I'm not talking about Amnesiac Furude Hanyū. No, I'm not talking about Mystery Novelist Hachijo Ikuko. Hell, I'm not talking about Goddess-form Hai-Ryūn Ieasomūru Jeda either. I'm talking about the Endless Witch of Theatergoing, Drama and Spectating Featherine Augustus Aurora with the City of Book's MC Army (which is capable of overwhelming powerlevel wankery and Universal Devastation), her meta-fictional transcendence (which grants her Nigh-Omniscience, Cosmic Awareness, True Flight and Invulnerable Meta-Immortality) capable of using Element, Text, Information, Vector, Matter, Space, Time, Causality, Death, Reality and even Plot Manipulation, equipped with her Repaired Horned Crown (capable of holding together her abstract form) and the Onigari-no-Ryūō because she is a master in kenjutsu and taijutsu, perfect Causality Transcendence (that can disregard all logic errors), control of both Existence Erasure and Creation, with alien Ryūn DNA and Rika's soul implanted on her chest, her Senate's forces guarding her and nine gazillion pieces of furniture floating behind her AFTER she absorbed all fiction from the multiverse, reached the Creator Boundary, started the Game of Games with everybody and used True Platonic Concept Manipulation so she could stop the mere idea of a threat while they entertained her.

Is there a character stronger than Auaurora?

And I'm not talking about Amnesiac Furude Hanyū. No, I'm not talking about Mystery Novelist Hachijo Ikuko. Hell, I'm not talking about Goddess-form Hai-Ryūn Ieasomūru Jeda either. I'm talking about the Endless Witch of Theatergoing, Drama and Spectating Featherine Augustus Aurora with the City of Book's MC Army (which is capable of overwhelming powerlevel wankery and Universal Devastation), her meta-fictional transcendence (which grants her Nigh-Omniscience, Cosmic Awareness, True Flight and Invulnerable Meta-Immortality) capable of using Element, Text, Information, Vector, Matter, Space, Time, Causality, Death, Reality and even Plot Manipulation, equipped with her Repaired Horned Crown (capable of holding together her abstract form) and the Onigari-no-Ryūō because she is a master in kenjutsu and taijutsu, perfect Causality Transcendence (that can disregard all logic errors), control of both Existence Erasure and Creation, with alien Ryūn DNA and Rika's soul implanted on her chest, her Senate's forces guarding her and nine gazillion pieces of furniture floating behind her AFTER she absorbed all fiction from the multiverse, reached the Creator Boundary, started the Game of Games with everybody and used True Platonic Concept Manipulation so she could stop the mere idea of a threat while they entertained her.

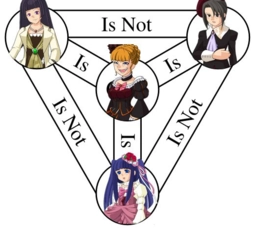

R:5 / I:4

ERIKANTRICE THREAD

Erikantrice is the theory that explain all umineko with 3 points:

1)same culprits for every game Kanon and George

2)ep5 and ep6 is explained with Erika=Kanon the detective fantasy of Yasu

3)Ikuko is Yasu all umineko is the magic version of her trying to make battler remember

READ HERE THE LATEX MANIFESTO

https://www.docdroid.n

ERIKANTRICE THREAD

Erikantrice is the theory that explain all umineko with 3 points:

1)same culprits for every game Kanon and George

2)ep5 and ep6 is explained with Erika=Kanon the detective fantasy of Yasu

3)Ikuko is Yasu all umineko is the magic version of her trying to make battler remember

READ HERE THE LATEX MANIFESTO

https://www.docdroid.n

R:3 / I:2

Ryukishi interview about Gou/Sotsu

https://07th-expansion.fan

Ryukishi interview about Gou/Sotsu

https://07th-expansion.fan

R:2 / I:1

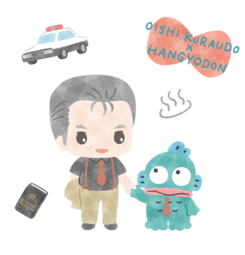

Pixiv had a Higurashi art contest

https://www.pixiv.net/contest/higurashianime

As is usually the case with art contests, I liked the stuff that didn't win more than the stuff that did.

Pixiv had a Higurashi art contest

https://www.pixiv.net/contest/higurashianime

As is usually the case with art contests, I liked the stuff that didn't win more than the stuff that did.

R:57 / I:24

Now the first arc is over, I think it's time for a Higurashi discussion and theorycrafting thread. Obviously contains spoilers for the entire series, I will be using spoiler tags but some things might slip by, so hide the thread if you care about that.

First, the struggle with Rena - I am inclined to believe that Keiichi hallucinated the whole thing. Needless to say, the scene itself is pretty ridiculous, what with Keiichi being repeatedly stabbed in the chest but still somehow managing to muster up the strength to bludgeon Rena with the clock several times. Later when we see him in the hospital, it's confirmed that he is a late stage HS patient, and his wounds don't match the state he was in when he lost consciousness - only his left cheek was grazed, and he had no neck injuries. Except for Ooishi confirming that something went down at his house on that night, none of the other characters allude to what really happened (understandable since Keiichi has just woken up from a coma.) Also, what happened to the neck collar? He's not wearing it anymore when Mion visits.

What the actual fuck happened to Tomitake, Takano and Irie? Takano shows up for only a few seconds, Tomitake shows up briefly but behaves the same as in Onikakushi, and since Keiichi doesn't go talk to them during the festival we don't see any more of them, and Irie doesn't show up at all and his clinic is being "remodeled". I think the most likely scenario is that Takano died for real (since the fake body wasn't found in the mountains and she is considered "missing") and the project was canceled, hence the "remodeling", but then I have no idea how she died. Since Tomitake's body wasn't found either, it's also possible that he wasn't injected with the HS pathogen.

Speaking of Takano, from the circumstances surrounding Rika's death we know it wasn't her who did it this time. I believe Satoko had a HS episode and Rika was forced to kill her, and then committed suicide by stabbing her own neck as seen in Meakashi.

Now the first arc is over, I think it's time for a Higurashi discussion and theorycrafting thread. Obviously contains spoilers for the entire series, I will be using spoiler tags but some things might slip by, so hide the thread if you care about that.

First, the struggle with Rena - I am inclined to believe that Keiichi hallucinated the whole thing. Needless to say, the scene itself is pretty ridiculous, what with Keiichi being repeatedly stabbed in the chest but still somehow managing to muster up the strength to bludgeon Rena with the clock several times. Later when we see him in the hospital, it's confirmed that he is a late stage HS patient, and his wounds don't match the state he was in when he lost consciousness - only his left cheek was grazed, and he had no neck injuries. Except for Ooishi confirming that something went down at his house on that night, none of the other characters allude to what really happened (understandable since Keiichi has just woken up from a coma.) Also, what happened to the neck collar? He's not wearing it anymore when Mion visits.

What the actual fuck happened to Tomitake, Takano and Irie? Takano shows up for only a few seconds, Tomitake shows up briefly but behaves the same as in Onikakushi, and since Keiichi doesn't go talk to them during the festival we don't see any more of them, and Irie doesn't show up at all and his clinic is being "remodeled". I think the most likely scenario is that Takano died for real (since the fake body wasn't found in the mountains and she is considered "missing") and the project was canceled, hence the "remodeling", but then I have no idea how she died. Since Tomitake's body wasn't found either, it's also possible that he wasn't injected with the HS pathogen.

Speaking of Takano, from the circumstances surrounding Rika's death we know it wasn't her who did it this time. I believe Satoko had a HS episode and Rika was forced to kill her, and then committed suicide by stabbing her own neck as seen in Meakashi.

R:3 / I:0

Of magical gore bits

Nothing is on the creature

For Maria in September

Witch is golden dreamer

It's magical Gohda chef

I'm gonna piss in fire

For magical breeding power

In the brewing party

Saw every everything

There he comes, breaking the darkness

George in grief

Yo, Master crazy

Saw every everything

In a way, I'm feeling

My broken artichoke

"Higurashi Sotsu OP2" Lyrics

My witch is golden dreamerOf magical gore bits

Nothing is on the creature

For Maria in September

Witch is golden dreamer

It's magical Gohda chef

I'm gonna piss in fire

For magical breeding power

In the brewing party

Saw every everything

There he comes, breaking the darkness

George in grief

Yo, Master crazy

Saw every everything

In a way, I'm feeling

My broken artichoke

R:0 / I:0

hat silhouette which

Began to grow distant

Will never turn back again

Even if the long night were to end,

The errors and the sins

Won't fade away—now or ever

With the setting sun,

The darkness creeps in closer

Dyeing all that is pure with black

The more I wonder, I ask—

Why did you test me with pain?

All I ever wanted

Was just one single thing—

Just that smile

All those days of making mistakes

Again and again—

We could take them apart

And put them back together in place

Even if you lose your way,

I'll set off to come see you

So come, wipe away all those

Heartbreaking tears

Before we even realized,

We had long forgotten

That tender voice of yours—

So let us search for it

If only we could bring ourselves

To take each other's hands again;

One more time—

Let's make a promise to each other

hat silhouette which

Began to grow distant

Will never turn back again

Even if the long night were to end,

The errors and the sins

Won't fade away—now or ever

With the setting sun,

The darkness creeps in closer

Dyeing all that is pure with black

The more I wonder, I ask—

Why did you test me with pain?

All I ever wanted

Was just one single thing—

Just that smile

All those days of making mistakes

Again and again—

We could take them apart

And put them back together in place

Even if you lose your way,

I'll set off to come see you

So come, wipe away all those

Heartbreaking tears

Before we even realized,

We had long forgotten

That tender voice of yours—

So let us search for it

If only we could bring ourselves

To take each other's hands again;

One more time—

Let's make a promise to each other

R:1 / I:0

Something I've been meaning to ask for weeks but always forget. Can anyone explain how Rika and Satoko's abilities are able to manifest concurrently? Up until now only Rika was looping, and my personal interpretation was that each fragment exists as a possible reality, but is only actually set into motion when Rika (or her consciousness, rather) enters it, since she is not shown to be able to live through multiple fragments at the same time. Now that Satoko has become a looper, how do her powers affect Rika and vice-versa? It seems at this point in time Satoko is more powerful and so I assume she would take precedence, but then what happens when Satoko resets while Rika is still alive, like the finger snapping thing in this episode?

Something I've been meaning to ask for weeks but always forget. Can anyone explain how Rika and Satoko's abilities are able to manifest concurrently? Up until now only Rika was looping, and my personal interpretation was that each fragment exists as a possible reality, but is only actually set into motion when Rika (or her consciousness, rather) enters it, since she is not shown to be able to live through multiple fragments at the same time. Now that Satoko has become a looper, how do her powers affect Rika and vice-versa? It seems at this point in time Satoko is more powerful and so I assume she would take precedence, but then what happens when Satoko resets while Rika is still alive, like the finger snapping thing in this episode?

R:5 / I:2

OK

explain this to me, if this were Hanyuu then why would she be portrayed in a somewhat menacing manner in the OP? If the series assumes you know it's a sequel then there's no reason as to why it would expect you to think that Hanyuu is in anyway evil. So therefore this has to be Featherine

OK

explain this to me, if this were Hanyuu then why would she be portrayed in a somewhat menacing manner in the OP? If the series assumes you know it's a sequel then there's no reason as to why it would expect you to think that Hanyuu is in anyway evil. So therefore this has to be Featherine

R:6 / I:2

I've come to the realization that Gou can be enjoyed 100% without having any knowledge of Umineko. While a bunch of it could be seen as Umineko fanservice that's more enjoyable after having read it, it's not at all a required reading to understand Gou. At most it gives context to hints that were scattered out throughout bonus scenes in Umineko that gave reference to Bern's backstory and the Higurashi connection.

Also it may even be better for those without having experienced Umineko as based off of context clues in it, one could infer that Rika is forced to kill Satoko

I've come to the realization that Gou can be enjoyed 100% without having any knowledge of Umineko. While a bunch of it could be seen as Umineko fanservice that's more enjoyable after having read it, it's not at all a required reading to understand Gou. At most it gives context to hints that were scattered out throughout bonus scenes in Umineko that gave reference to Bern's backstory and the Higurashi connection.

Also it may even be better for those without having experienced Umineko as based off of context clues in it, one could infer that Rika is forced to kill Satoko

[Refresh] [Top] [Index][Archive]